Why not digital? Technology as an interagency tool in the Central African Republic

The conflict in the Central African Republic (CAR) has been raging for over a year with violence, often linked to religious affiliation, involving rape, murder, torture, pillaging and the destruction of property. The scale of the emergency is immense: according to OCHA, as of 11 August 2014 an estimated 2.5 million people out of a total population of 4.6m are in need of humanitarian assistance, and a fifth of the population (almost a million people) have been displaced.

Humanitarian workers are having difficulty meeting these needs. Interventions are severely underfunded, and agencies are struggling to register beneficiaries and distribute commodities, with chaotic and sometimes violent distributions, double dipping, forged ration cards and theft by staff and beneficiaries alike. To help address these problems, World Vision’s Last Mile Mobile Solutions (LMMS) platform was piloted in CAR.

What is LMMS?

LMMS® is a suite of innovative technology applications aimed at improving the effectiveness, efficiency and accountability of humanitarian action. In operation for over six years, it was developed by World Vision in collaboration with humanitarian agencies and the IT industry. LMMS digitizes beneficiary registration, reporting and tracking in real-time, functioning in locations where there is no electricity or internet, often in the middle of crisis situations.

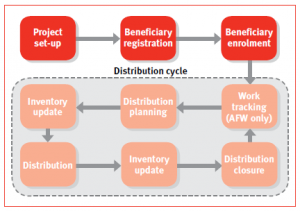

LMMS has the following steps:

- Project set-up: This step defines the type of project (e.g. general distribution, aid for work), duration, ration size, donor).

- Registration: Household members are digitally registered. Individuals receive their own unique bar-coded entitlement card with a photo. LMMS creates a single beneficiary master list.

- Enrollment: Households or individuals are enrolled in projects defined in the project set-up. Households can be enrolled in multiple projects without repeat registration.

- Work tracking: LMMS captures the number of days worked (for aid for work projects) in order to calculate wages due.

- Distribution and inventory management: Material entitlements are automatically calculated for distribution planning. During distribution, cards are scanned to determine eligibility and individuals are visually matched using photos stored in the database. Physical inventory is tracked in real time as commodities are distributed, or if cash is being provided payment agents can be instructed as to whom to disburse payments to. Distribution reports are generated in near real-time including total households and individuals reached, disaggregated by age, gender and vulnerability as well as total commodities distributed and loss reports.

With support from the Canadian government, LMMS has been made available to the wider humanitarian sector for improved beneficiary registration, monitoring and reporting, and to demonstrate the viability of shared and scalable technology platforms at the last mile where aid reaches people in need.

Users include Oxfam GB, Medair, Save the Children, CARE, the Norwegian Refugee Council, Food for the Hungry and Mercy Corps. LMMS has been deployed in 23 countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America, registering close to half a million households and over 2m beneficiaries, with plans to deploy in 30 countries, reaching at least 4m beneficiaries, by 2015.

LMMS pilot in CAR

A member of the LMMS team arrived in Bangui on 22 April 2014 carrying with him equipment for the piloting of LMMS in CAR. He held demonstrations and meetings with clusters and agencies, including the Camp Coordination Camp Management (CCCM) cluster, the food cluster, the shelter cluster, Premiere Urgence, Welthungerhilfe (WHH), the Danish Refugee Council (DRC) and the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC). He also observed a food distribution in Bangui to see first-hand the challenges faced by agencies in CAR. The distribution was cumbersome, with a paper registration and distribution process requiring beneficiaries thumb prints to prove receipt of relief items. It was then agreed to pilot the LMMS system with the Danish Refugee Council (DRC), which had a food programme in Bangui.The LMMS team installed, configured and set up the LMMS system over a weekend. The configuration included setting user access rights and location data. A two-hour training session was held on the morning of Monday 28 April with DRC staff on the LMMS registration application. The same afternoon the staff registered over 500 beneficiaries in a camp for Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in Bangui.

The initial food distribution delivered rice, lentils, plumpy nut supplement (a peanut-based supplement used to treat severe acute malnutrition), salt, CSB (corn-soya blend) and vegetable oil to over 600 people.3 At the distribution, because the LMMS processed beneficiary data faster than people could take their rations, processing occasionally had to be paused. The efficiencies brought by LMMS led DRC to start rethinking its entire food distribution workflow process. One consideration was the opening up of multiple reception points instead of having a single one.

One of the advantages of the LMMS system is that there is a validity check during the distribution. During this particular distribution, for example, the system flagged an attempt by an individual to take double rations. Finally, during the first distribution, DroidSurvey, a forms-based offline survey tool used for data collection research on Android tablets and smartphones, was loaded onto the same mobile devices that ran LMMS. This allowed staff to survey a sample of the population for greater accountability and to learn about the experience of the aid recipient through the process. Beneficiaries were asked questions related to their experience with LMMS, how it compared to the previous manual process and whether they objected to having their photograph taken as part of the registration process. They were also asked for feedback on the quality and quantity of the commodities received. The feedback from beneficiaries showed a high level of appreciation for the speed and accuracy of LMMS, when compared to the manual process previously used. None of the respondents indicated that they objected to having their photograph taken, and in fact welcomed the use of the LMMS ration card as it gave them a sense of empowerment.

Further registrations, distributions and surveys were undertaken by DRC throughout May 2014. An additional 4,700 people were registered during this period.

Interagency capacity and data sharing

In the same IDP camp where the DRC was conducting food distributions, World Vision (WV) was also distributing non-food items (NFIs). There was no need for WV to undertake another registration exercise since the data set from the DRC registration could also be used for the WV NFI distribution.

The sharing of data between agencies saved a great deal of time and demonstrated the benefits of using digital systems such as LMMS as multi-agency multi-sector tools.

Challenges

One of the challenges highlighted by the pilot is how to incorporate digital technology such as LMMS in the midst of a project or funding cycle. It is often difficult to allocate resources and make staff available for activities such as training once a humanitarian project has been launched. While it is preferable to deploy LMMS at programme inception, mounting evidence from active deployments points to cost savings of between 15% and 40%, and thus some organisations in CAR, such as Cooperazione Internazionale (COOPI), have chosen to adopt LMMS in mid-cycle to harness the operational efficiencies and savings that LMMS delivers.

Several beneficiaries raised data privacy concerns. They wanted to know what would happen with the personal information that was being captured by the system, even though LMMS has built-in functionality to seek and capture informed consent. In most contexts these are very valid concerns, but they become more pertinent in a volatile situation such as CAR. It is thus important for agencies to have very clear policies and protocols on informed consent and data privacy and protection, and to be able to communicate them to beneficiaries.

The use of LMMS, especially when transitioning from paper systems, highlighted the need to adjust the layout and flow of the distribution process. Changes such as the pre-packaging of individual commodity kits, while a little more costly, are much faster than the practice of group sharing. A balance needs to be struck between the increased efficiency (and time savings) brought about by digital systems and the incremental cost of making adjustments to the distribution process.

It is also important for agencies to understand the limitations of the digital tools they acquire. A number of agencies in CAR, while seeing the value of LMMS, expressed a need for additional functionality that the system was simply not designed to provide, such as surveys. With the increasing number of digital solutions being made available for aid agencies, LMMS is envisioned to be a key cog in a suite of digital tools operating at the last mile.

Conclusion

The LMMS pilot with DRC was well received by humanitarian agencies and beneficiaries alike. The pilot demonstrated that digital systems such as LMMS can increase the effectiveness, efficiency and accountability of humanitarian programming, provide better services to beneficiaries by way of faster-moving, shorter queues and can be deployed quickly with minimal training in an emergency context. As a consequence, beneficiaries have more time to attend to pressing daily needs as opposed to standing in line for hours waiting to be served. Digital systems can also increase the productivity of field staff, enhance the accuracy and timeliness of data, potentially reduce fraud and increase value for money (achieving more with fewer resources). The CAR deployment gave a taste of a future scenario where infrastructure can be shared across multiple agencies, increasing sustainability for the investment with multiple agencies being able to use the same technology platform. This naturally leads to the development of a shared services model of technical support staff, as opposed to every agency having a dedicated team.

More work remains to be done to increase the digitisation of the humanitarian sector. Standardisation of data meaning and structure will be key for cross-system integration as more humanitarian players make the transition to digital systems. In addition, concerns over data privacy and protection need to be addressed; consideration should be given to adopting guidelines and tools developed by the Cash Learning Partnership (CaLP) instead of having each agency attempt to develop their own protocols.

In the wake of the LMMS pilot in CAR, interest among agencies operating in the country has been high. COOPI has just deployed LMMS, and further deployments are planned with a number of agencies to increase the scale of digital technology deployments and inter-agency capacity in CAR and elsewhere. More important, however, will be engagement with donors, clusters and humanitarian players on defining data standards, protocols on informed consent, data sharing, data privacy, agreement on normative standards of accountability (clear benchmarks for accountability towards beneficiaries and donors alike) as well as the continuation of evidence-gathering activities that show the value and impact of digitisation.